Nontraditional Covid indicators

Flying blind on anecdote

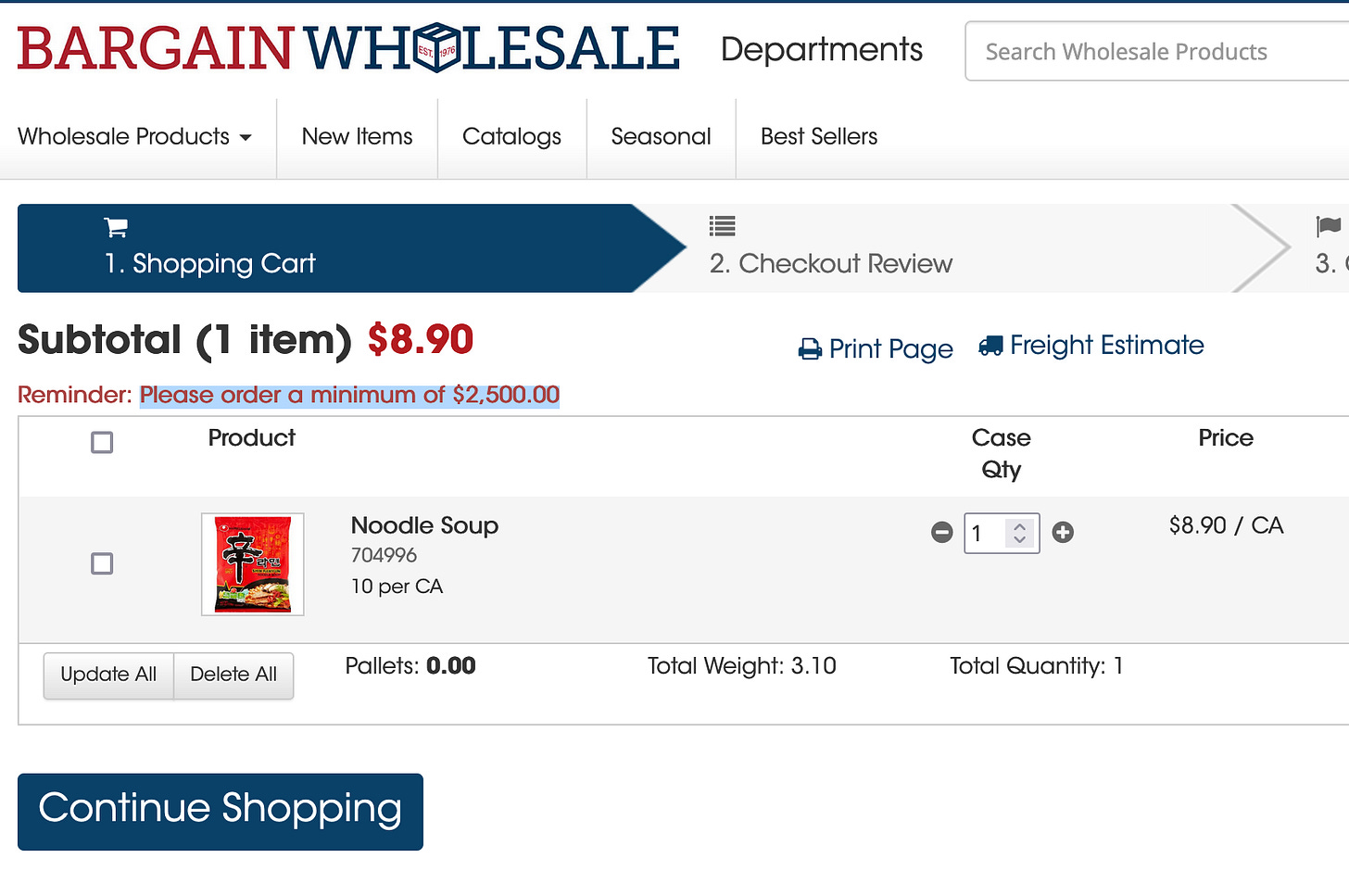

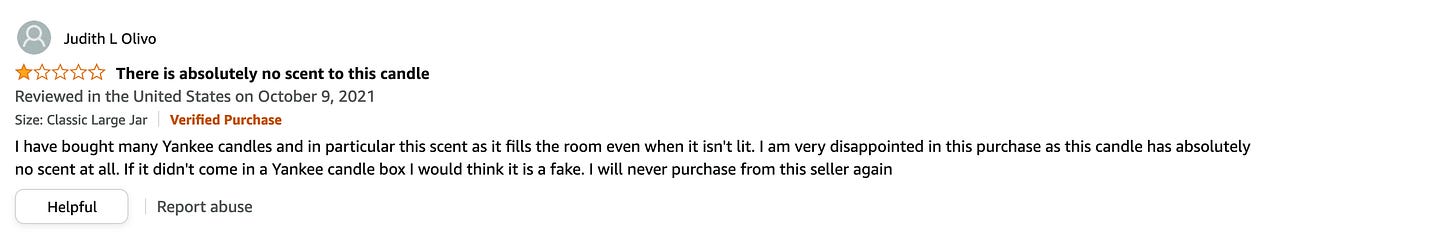

Sometimes if I’m not online much, Rob updates me on news from the internet, and when I’m spending too much time online I update him, and so I feel content in assuming that a few of you have real lives, and don’t know about the unofficial, half-joking measures of covid rates. Testing is imperfect anyway—not everyone infected gets a test, and not every area tests at similar rates. So scientists check the sewage for covid DNA, as you’ve likely read. Likewise, internet figures check the rate of one-star reviews of Yankee Candles, for complaints that the notoriously strong-scented candles don’t smell. They also note shelves that are emptied of saltine crackers. (You know, crackers you eat when you’re sick.) Me, I’ve noticed a lack of ramen in grocery stores, at least once a cashier pointed it out. I’ve been on a weeklong quest to buy Shin ramen in bulk, to gaps in shelves. Luckily, I found a guy.

Unofficial statistics reinforce just how shaky a foundation we rely on to envision the big, global-scale issues in which our lives are embedded. This is especially true of social trends. While we can try to distill complex reality into numbers, stats are only as good as the data they start from. I’ve worked on business papers that take a goofy questionaire with a small sample size, then process the results through layers of calculus and linear regressions until, yes, they have very convincing evidence of a trend, but the data still reflects how hand-picked CEOs responded to multiple choice questions about “leadership.”

Hard data is better, of course—DNA in sewage is more irrefutable than voluntary one-star Amazon reviews. Temperature data is a hard number measurement, more reliable than animal population surveys.

Numbers like crime statistics depend on police reports. Since the introduction of statistic-driven policing, cops became notorious for misclassifying, say, a burglary as “lost property,” for better stats.

A preponderance of anecdotes also paints a false picture. The New York Times keeps writing about how citizens fear street crime—but New York homicide rates are 50% lower than they were when Giuliani left office. Crime in this country is at historic lows, but brains don’t internalize data tables—stories carry more weight than the statistics they belie.

As police departments push for more funding, or rally against bail reform, they feed newspapers anecdotes rather than numbers because statistics show low crime rates in cities like San Francisco.

Accurate crime rates aren’t important on their own. They matter because statistics inform our understanding of relationships between crime and societal choices. A letter in the Economist from two Statisticians in Denver said that shootings tend to happen on the same intersections, despite demographic changes. They write:

Violence is concentrated in specific places year after year, which strongly suggests that the use of land, built environment and place management all jointly support violence in those areas.

I don’t know if I agree with it, but the point of good recordkeeping is to help citizens decide whether the best crime prevention will be gun control, poverty reduction, more policing, or urban planning.

As I was about to publish this, Rob told me news from the internet: a Syrian immigrant New Yorker found the Brooklyn subway shooter. The NYPD counterterrorism unit was nearby, clearing out a homeless camp.

Be careful when remembering statistics start uncategorized in a messy world. The worst resolution would be to conclude that reality is optional and we can never know anything for sure. If you’ve ever read Orwell’s Politics and the English Language (best followed with D.F. Wallace’s brilliant, “Authority and American Usage”) you’d know that fascism needs people to lose faith in truth. Without a shared reality to discuss, democracy can not thrive. Fascism, however, doesn’t need a shared reality, not even a shared false reality. It just needs people to feel like they can’t trust anything. Then all that’s left to trust is the power of a politician.

Anyway, humans have to compose a picture of our universe and how its pieces push on each other. It’s funny how hard it can be, to send out our scientific feelers to the world beyond this moment, decode our reckless sonar, and map reality.

Trenchant analysis. Especially the conclusion that Fascism only needs people to trust power. Why worry when someone else will do it for you and “take care of it”?